Kiro Urdin – Films

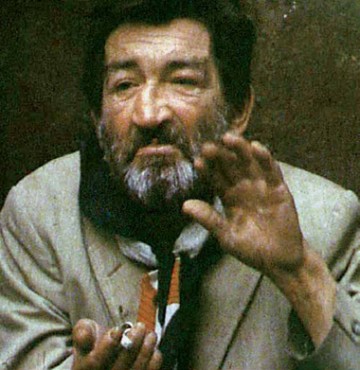

As part of this year’s Skopje Summer Festival, four films by Kiro Urdin were shown in the Mala Stanica venue of the National Gallery of Macedonia by way of homage to this distinguished artist. The Skopje public had the opportunity of seeing his films Planetarium, Dogs and Trains, Dogona and Pishta. The painter and film director Kiro Urdin lived and worked in Paris from 1974. He is one of Macedonia’s best-established and best-selling painters, who in the past decade has also been engaged in film making.

In the case of Kiro Urdin what we have is a different, indeed a rare artistic feat – or rather, the combining of two artistic feats into one: painting and film. Yet neither Kiro Urdin’s ideas nor his impulses end with the camera or his paintbrush. He goes much further, exploring and interpreting life, filming it and painting it in all its radiance and its spectrum of colours. In world-wide terms Urdin is to be numbered among the leading cosmopolitan artists, globe-trotting documetors of the planet Earth.

It is in this sense that Dogs and Trains poses the question: What is it that is closest to art – that which cannot be understood or that which is impossible? This is how Urdin introduces the age-old topic of the link between art and life. He does not shy away from stating his own scruples about our modest capacities, our imperfections. On the contrary, he counters them with dimensions of his own reality, spontaneity, spirituality, timelessness and infinity, categories experienced to a certain extent but not fully comprehended. A painter need not necessarily travel far to portray his daydreams and imaginings, the pictures already prepared in his mind, but Urdin as an artist wants to feel the concrete, bare, vital experience of travelling, of space, of authentic knowing, to draw upon the diversity of civilisations, to make contact with the essence of life… and of death. And what can be more disturbing, more thrilling and more enlightening than the wisdom of the Dogon people: a celebration in honour of death?

And yet this idea was conceived long ago at a time when the young Urdin was wandering through Montmatre, when the clochards of Paris were to be numbered among his friends, when he filmed Pishta, a poor soul, an urchin dear to God but now grown old, whose act of self-immolation could not be interpreted otherwise than as a celebration of the birth of death, a revelation and a liberation. So it was that, twenty-seven years after shooting the first sequences of Pishta, Urdin brought us Pishta the clochard’s departure for paradise. And Venko Serafimovski was to illustrate it discreetly and elegiacally with his own piano version of an ode to Bohemians, not in the style of Beethoven, but his own appropriate Ode to Street Innocents.

Two years later, when dogs and trains crossed paths, Urdin registered that magical and cyclical passage of fate: Illusion is a Mystery, Mystery is Reality, Reality is Illusion. And the obvious truth that we are all thirsty for water, but also the well known metaphor that only love thirsts for fire. And it is precisely that love, as the rudder guiding Urdin throughout his creative quest, that succeeds in kindling the fire of the world, in revealing the radiance of Earth’s globe, a radiance visible only from other planets.

Urdin’s films awaken in us our dormant sentiments of and need for companionship among people, remind us of the almost forgotten tactile forms of communications. Urdin is something quite rare among creative artists: an obstinate optimist, an incurable apologist for beauty, art and life. Yet he is no ideologist of joy but a realist, an artist of flesh and blood whom this planet has taught to respect death, too, as much as he does life.

In this context it is only right and proper to mention those people without whom Urdin’s films might have been other than what they are: Ivan Mitevski – Coppola, as the director of Planetarium, the cinematographer Vladimir Petrovski-Carter and Venko Serafimovski, mentioned previously, the composer of the music/sound track in the majority of Urdin’s films.

For Urdin humanity is his motive, art his tool and love his message. This is Kiro Urdin’s Planetarism, the building of civilisational bridges between cultures. In shooting Planetarium he assembles on the screen, his canvas, traces of the sky over Berlin, the marble of Sacré Coeur, the milk of the shewolf of Rome, the ashes of Pompeii, the waters of the Ganges and the sands of Africa . . . all of these traces of this world on a single canvas, all thoughts in a single space . . . and the message is love.

Vlatko Galevski