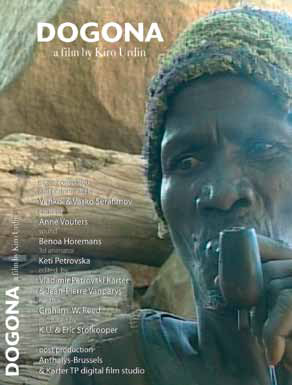

Kiro Urdin – Dogona

Where were they to go. By water or by land. There was sunshine everywhere. Every day. And stars too. Sometimes mothers collected the stars in wooden vessels and gave them to their children. To the north was the River Niger, and it seemed to the oldest Dogon that at the time of his brother’s funeral Nomo was whispering to him and making it known to him.There, in the north, lies Bandiagara. On the river bank the crocodiles are waiting to carry you across to the other side. To the chaos on the steep, stony bank. There are the rocks of the Tellem, the bird people, the great wizards of the realm of spells. Indeed, they appear from time to time as a sandstorm with a herd of wild animals or with the white fox.

That’s how the Dogons got to Bandiagara. Here in the massif of the Yugo the first Sigi began, in honour of the first one to die. The masked dancers danced every sixty years recalling the moment when death was first born. Olobolu, the dancer with the big snake mask, leapt about with a marvellous lightness while his soul was full of Ama, Nomo and the eight ancestors.

It seemed as if the prayer of the oldest Dogon was issuing from the great mask as he lifted up his arms towards Nomo and the other ancestors. He prayed that rain would fall, that the fields sown with onions, rice and corn would be watered. That the pregnant women would have easy births. They believed in the power of the almighty, who had succeeded in uniting space and time. He knew from what his grandfather had told him that only the body can die, the spirit not, that it was a part of Ama. Neither could it die, nor be born. He gazed at the sacred paths. The spirits are here, around us. They see us, they love us, but they also punish our sins. That’s why you must always take care. Everything has a soul. Even death. Life and death live side by side, like the earth and the sky.

He went barefoot all his life. He felt neither stones, nor sand, nor thorns. His skin was as hard as the drought. The eight totems protected him from everything. Even from thirst. Less and less rain fell. Sometimes, in Bandiagara, during the days of the Tellems, the great wizards, there were herds of antelopes, lions and leopards. But they’d all vanished because of the drought. The plants, insects and birds too. The sand had become their graveyard. Everyone was praying for rain. Even the dead. From time to time the Tellems appeared as a sandstorm, accompanied by their vanished herds, or in company with the white fox. But the Dogons remained here, their spirit survived. The rice continued to grow and ripen to harvest. The onions too. The skilled hands of the Dogons went on fashioning figurines and masks.

The mornings, when the darkness still clung to the landscape, the infants, grown one with their mothers’ backs, mutely watched the first blows of the mattocks. The fields had to be sown. The first rains had only just fallen. And their older brothers and sisters were still sleeping without a care in the world under the mantle of the stars.

Then his grandfather went on with his tale: Before the time of Doyogu-Seru, the first man to die, death had not existed. That was why the Dogons made the great snake mask, in honour of the birth of death. When you were born – continued his grandfather – the rains dried up for three years. The sun grew bigger each day. By night new stars emerged. It began to seem to the Dogons as if they slept on stars, there were so many of them. The women stopped wailing over death and instead of weeping over it they wept over thirst. But the dancers were here, the masks, the figurines with their arms raised to Ama, to Nomo, the dead ancestors whose spirits, living here beside them, the eight living totems which protected them – the living power of Nyama.

Thirst gave way in face of that protecting power. So the plants did not dry up, the infants grew, only the birds didn’t fly, the air was too hot. Soon heavy rains fell. The livestock were watered after such a long time when not a drop of rain had fallen.

Dolo remembered when his grandfather had died. It was May. The masked dancers wove in a spiral around their house. The dead body of his ancestor was placed in a freshly hollowed-out tree trunk on the verandah, and in a trance the oldest Dogon explained, by means of mime, the symbols and the genesis of the cosmos. Night had long since fallen and it was as if the almighty Ama was riding on its shoulders. At one moment it seemed to him that the eight totems were sitting on his grandfather’s body, exchanging greetings with the spirit that had not yet left his body.

Dolo was captivated by the dancers, the masks, the figurines, by the mannikin of death, and the sacrifice was brought out, that meant that Nomo was here too, Ama was there. And all the ancestors. Space had merged into a single point. The stars, wind, fire, water and time too. From the other side the sound of tools could be heard. One of the neighbours was completing the sculpture which was to be sacrificed. On the other side of the fence the children were drawing something incomprehensible. That morning they had hoped that the white fox would pass across the picture so that the holy ones could figure out the augury. And the children drew and played innocently and purely as their childlike hearts bade them.

Dolo recalled the words of his grandfather. Death has a soul, he said, everyone has a body and several souls, and a living power, and is born and lives in water. It is everything. When a baby is born, it drinks water through the milk. Before death the old people ask for water. Everything is born in it: light, wind, earth, even fire. Plants, insects, birds. The soul. Even the deserts are created by water. At night, when everyone is asleep, water is transformed into a bird with enormous wings that flies over Bandiagara. In the morning it vanishes with the sun. And when Ama decides the sand can be transformed into rain, the desert into a sea. Life flows for a time, joy returns, men love only water more than their women. But when it vanishes, fear puts in an appearance, pain, hunger, thirst… Dolo felt happy at all this. His soul laughed. Death seemed to him to be the shadow of Sirius, lying upon the body of his grandfather. He rejoiced in the dancers’ airy leaping. And the spirits of all the other dead were there somewhere in the offing. At dusk they would have to set off for the marvellous land of the ancestors, to the realm of the holy spirits. Everything was everlasting that night, the spirits could neither be born nor die.

The universe of immortality was gathered into the eye of Ama.