Kiro Urdin – Planetarium Movie

THE PLANETARIUM OR ONE MAN’S ODYSSEY

If to leave is to die a little, Kiro Urdin who arrived in Paris in 1973, bereft of everything, started his resurrection after three months spent almost in a tomb, a cellar lent by a compatriot, where he lived obscurely during his first weeks in the City of Light. In order to survive, he managed to paint portraits of tourists on the place du Tertre, tourists who wanted to see themselves in paint so as to believe they are characters. But doing this without permission meant that Kiro lost his work permit, and found his fate: since he was not allowed to paint to live, he decided to live to paint. So he chose this path, out of all the image-making arts in which he is adept.(he practiced law in Belgrade, and studied visual arts and cinema in Paris). But the masterpiece he is most proud of is not a picture, and he is only half its author: she’s called Donna, by virtue of a baptism, carried out in her father’s native land, in the church of Orhid in Macedonia, situated beside a lake shaped like the beginning of the word. A church with blue vaults lit up by frescoes, similar to the sumptuous frescoes in Nerezi, announcing Giotto as early as the 12th century. This inspired Kiro Urdin to undertake his project to create a heavenly vault for the end of the 20th century which he calls Planetarium.

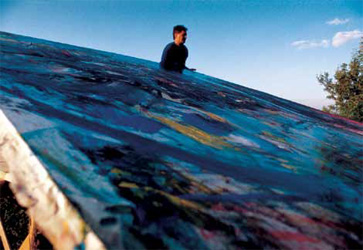

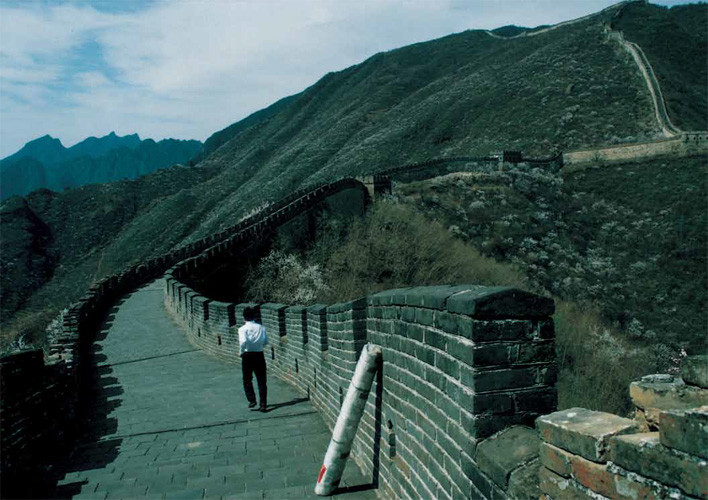

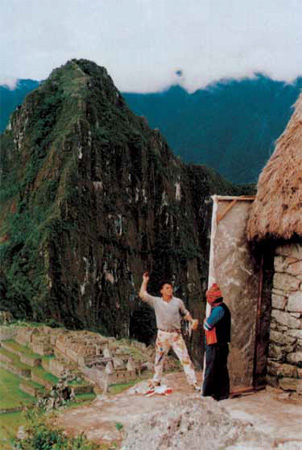

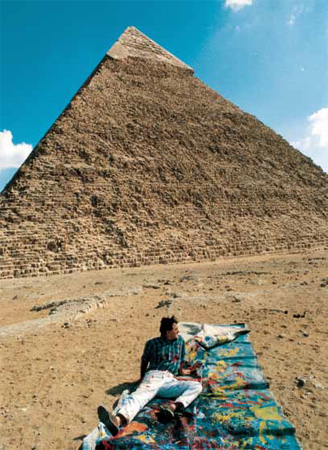

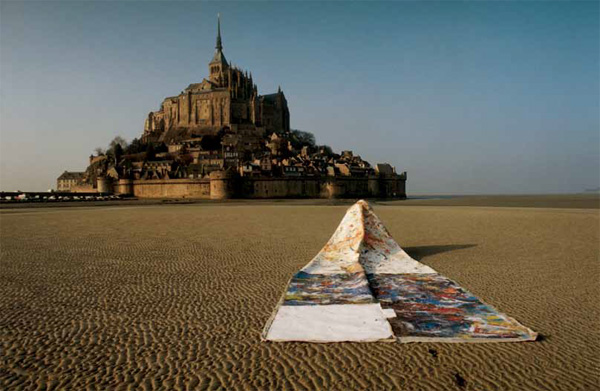

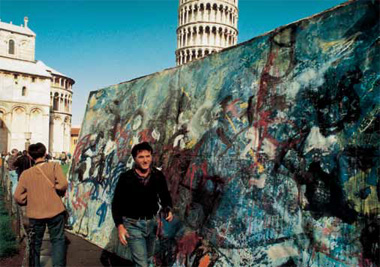

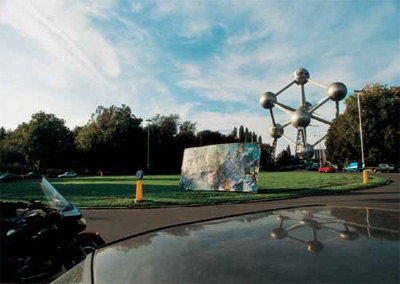

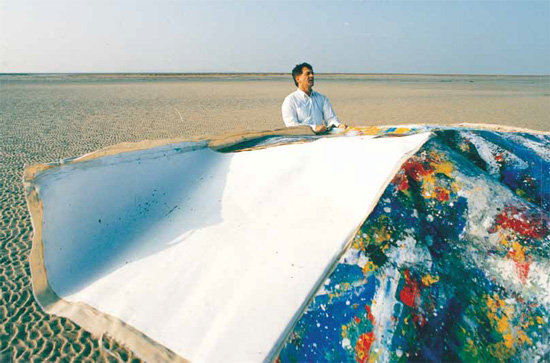

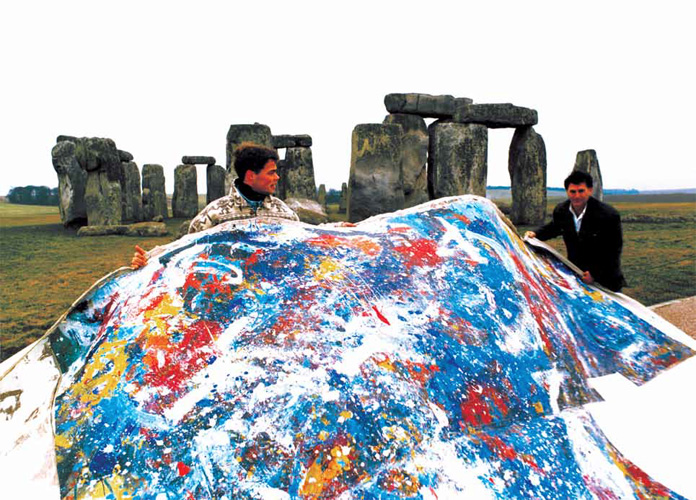

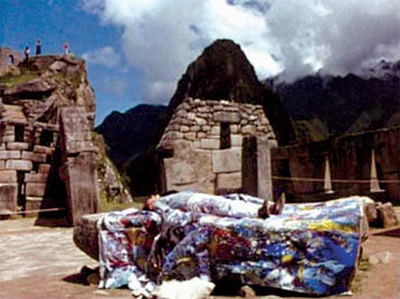

One becomes godlike when one becomes a father: Kiro was ready to create the sky and the earth for his little daughter’s wide eyes, open to every mystery. And off he went, travelling the world, but not in order to bring back its images to lay at the feet of the child, because an abstract painter only ever shows his inner world. So as to show his secret heaven, he wanted to climb the topmost rungs of the art word, all the places where heaven is the subject matter. Determined to go under every sky, unrolling his canvas, to see if a few little stars might land on it.

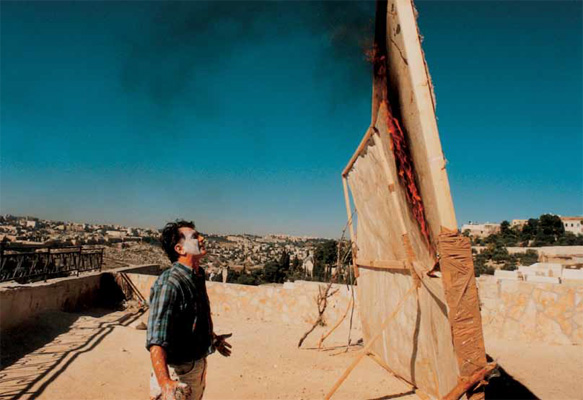

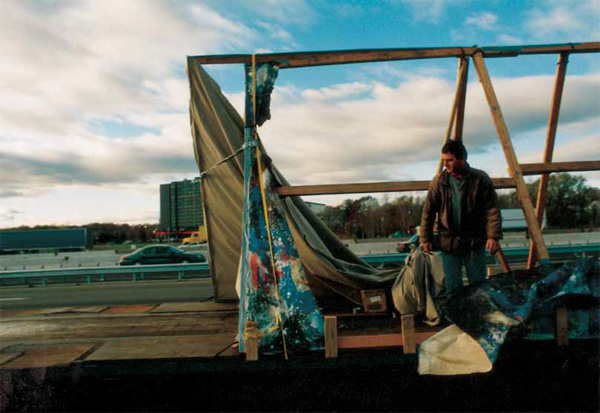

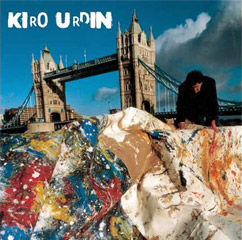

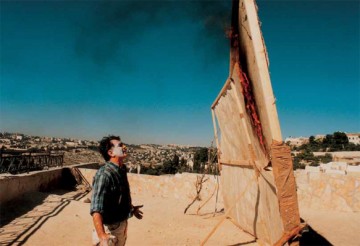

And so he covered many of these sacred places on the planet, from the Pekinese Temple of the Celestial Peace to the Leaning Tower in Pisa, from the stones of Stonehenge to those of Machu Picchu, from the Egyptian pyramids to the one in the Louvre, from the Masai Mara huts to the pagodas in Kyoto or Nara, from the Buddhas’ golden smiles in Bangkok, to the petrified sighs of the children of Pompei…. All the famous sites saw this figure, like a carpet dealer, a man carrying his roll of immense canvas on his shoulder, and it was a flying carpet. The artist was seen at work everywhere, obsessed by his visions, painting endlessly, exalting his life, a merchant on his carpet starred by colours, even lying on this amazing shroud unrolled in Gethsemane, just before he got the idea of setting fire to this burden, which perhaps weighed like a secret cross on his shoulder: in Jerusalem he immolated this attempt at heaven, to find out what might appear in the emptiness between the burnt edges of the canvas holding all his journeyings.

When he is not at the ends of the earth, Kiro works in his studio, walking over ladders placed flat on the canvas stretched on the ground, as if once could climb horizontally, as if seeking to reach inner stars.

And now the vision has arrived home, in the Neways building where the two canvases are hung. One is finished, it looks more like a planisphere than a planetarium: strange coloured continents seem to float on the oceans of the blue planet, like a satellite vision, taken from a dream space ship, from which one could make that heaven come true. But maybe we only see what we believe.

The other panel of his work arrived, infinite, and Kiro finished it on site, tracing in red the huge networks of blood vessels of vital circulation around a circular central pocket, and in that belly one might discern a foetal shape. And here we find Donna again, starting to walk, having come along, wit her mother’s help, to place her little paint-stained feet on the canvas, so that her first steps could become imprints, taking part in the manufacture of the red work. Going over the course of her life, from her mother’s womb to her meeting with the blue painting, the whole earth travelled by her father to find her. From the far-off interiors, where to come back is to live.

Jean-Claude Canevet